ECA INSIGHT >>

In February, the European Parliament’s Environment Committee voted in favour of the block introducing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), passing another milestone on the path to the world’s first such measure imposing a carbon price on certain imported products with high embedded emissions. As well as addressing concerns associated with European competitiveness and emissions leakage, the mechanism aims to encourage emissions reduction activity by trade partners. Careful design with regard to how embodied emissions of imports and abatement policies of trade partners are accounted for by the mechanism will be critical in achieving this objective. There is an opportunity for trade partners to review and reconfigure existing regulations to align with the CBAM to minimize the burden of the mechanism while simultaneously incentivizing abatement.

Extending carbon pricing to imported goods

The European Union’s (EU’s) CBAM will require importers of certain high carbon goods to pay the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) price equivalent for emissions embodied in the imports. The primary purpose of the CBAM is twofold: protect the competitiveness of EU industry and manufacturing once free allocation of EU ETS units are phased out, and to prevent carbon leakage caused by production shifting from the EU to countries without carbon pricing regulation. Such a mechanism is justified on the grounds of differences in ambition in emissions reductions between the EU and the rest of the world.

The CBAM will impose a negative impact on exports for near neighbors

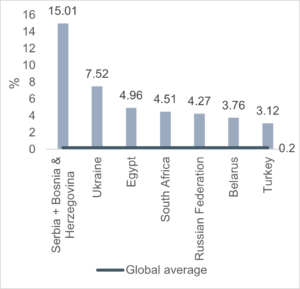

Europe’s near neighbors are expected to experience the largest impact from the CBAM on a per unit export basis because high carbon exports to the EU make up a relatively large share of their total export basket. Recent analysis by UNCTAD estimated that 6 of 7 countries with the largest reduction in exports as a result of a CBAM are in the Europe & Central Asia (ECA) and Middle East & North Africa (MENA) regions.

Figure 1 % reduction in exports for the 7 countries most impacted by CBAM

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2021. A European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Implications for developing countries.

The CBAM will also aim to incentivise emission reductions in these countries.

Additional to preventing emissions leakage, the CBAM aims to be a “climate tool to push third countries to adopt more stringent climate measures” [1]. However, careful design of the CBAM is required to create incentives for abatement in third countries. Should the CBAM not lead to third country abatement then even in the best-case outcome any substitution of high carbon to low carbon goods within the EU may have a rebound effect as the CBAM does not ensure high carbon goods no longer imported to the EU are not consumed elsewhere. At worst it could result in a transition from raw high carbon materials covered by the CBAM being imported to the bloc to downstream products manufactured using those goods, but not covered by the CBAM, being produced outside the bloc and subsequently imported, thereby having no impact on emissions.

Proposed design implies that third country carbon pricing is being prioritized

The CBAM aims to avoid double counting of carbon pricing by taking into account explicit carbon pricing policies in trading partner countries. However, it will not account for non-carbon pricing regulatory measures aimed at emissions reductions. This could incentivize a transition from other forms of subsidy for mitigation projects to adoption of a carbon price in relevant sectors.

Accounting of embodied emissions is critical for incentivising abatement

Accounting of embodied emissions under the CBAM is intended to mimic the EU ETS as much as possible. As such, importers of CBAM covered goods will have to surrender import certificates based on actual emissions. Measurement of actual emissions may, however, impose undue administrative burden on importers, particularly if EU standard monitoring, reporting, and verification standards are required. As such, default values for imported goods will be established.

Use of default values implies the central tenant of carbon price paid equaling marginal abatement cost may be violated

Carbon pricing is considered to be economically efficient in that it will lead to the marginal cost of abatement being equal for all polluters because those polluters will be incentivized to reduce emissions up to the point where the marginal cast of abatement equals the carbon price. Under the methodology proposed for accounting embodied emissions under the CBAM, there are two situations where this condition may be violated.

Firstly, firms in countries with very high emissions intensity of production that is higher than the default value will only be rewarded for emissions abatement once their emissions are below the EU average. In many ECA and MENA countries this may be prohibitively difficult and/or costly, particularly considering the energy mix, resulting in limited incentives to reduce emissions.

Secondly, for firms with emissions below the average benchmark but located in countries without the MRV infrastructure to cost effectively demonstrate their actual emissions, emissions reductions will not be rewarded and will effectively be double counted: once through the actual cost of abatement and again through the carbon price under the CBAM.

This second issue will be exacerbated by alternative incentives (regulation and financial) for mitigation actions not being accounted for by the CBAM. For example, a firm operating in a country imposing direct requirements on production processes that reduce emissions but increase costs would not have that cost accounted for in their CBAM payments. Likewise, firms operating in countries with taxes or levies that act as a de facto carbon tax by increasing costs of polluting activities, such as excise taxes on fossil fuels, will not have these costs accounted for in their CBAM bill.

Reconfiguring existing regulations can support emissions reductions in a manner accounted for by CBAM.

A priority for countries expected to be significantly impacted by the CBAM should therefore be to review relevant regulation with the objective of identifying opportunities that can reduce the burden imposed by CBAM and ensure domestic abatement costs are accounted for under the scheme. In particular, this might include identifying taxes, levies, and duties that can be restructured as a carbon payment. For potential accession countries in Eastern Europe, such a review can yield a double dividend by supporting alignment with the EU ETS, a necessary requirement for accession.

However, in many of the most CBAM exposed countries fossil fuels are subsidised (rather than taxed) and forward planning is needed to avoid a major shock.

Many MENA and ECA countries currently subsidise fossil fuels for some or all of power generation, heat, and road transport. For these countries, repurposing of existing taxes, levies, and duties will not be possible. To avoid a major shock at the introduction of CBAM, early planning for reconciliation of these subsidies with incentives for decarbonisation will be essential. Effective decarbonisation incentives in an environment with fossil fuel subsidies must take the form of non-price regulation, which will not be recognised by CBAM. Furthermore, any fossil fuel subsidies on inputs to EU exports would effectively be passed through to the EU rather than lower the cost of production, thereby constituting a payment from the domestic taxpayer to the EU treasury rather than generating domestic carbon revenues for recycling in the local economy. As is the case where existing taxes can be repurposed, reconciling fossil fuel subsidies will be of particular importance for accession countries where alignment with EU requirements on both fossil fuel subsidies and carbon pricing will be required ahead of joining the block.

[1] European Commission. 2021. Impact Assessment Report. Accompanying the document Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism

Will Wright

Senior Consultant

Will is an economist with over 8 years’ experience as both a research economist and an economic and strategy consultant. His work at ECA is centred in our Decarbonisation Strategy practice where he advises on policies and strategies for growing renewable capacity, closing coal, and putting a price on carbon emissions. Across his career Will has provided policy advice relating to environmental issues including water management and decarbonisation and he has experience across the agriculture and energy sectors. His previous clients include large global energy companies, regulated utilities, government, and international organisations.