ECA INSIGHT >>

ECA, in collaboration with E4tech UK, recently completed a multi-part study[1] for the Energy Community Secretariat (ECS) on the potential for hydrogen utilisation among its Contracting Parties (CPs). Our study includes an assessment of recent hydrogen developments and the CPs’ readiness for integrating hydrogen into their energy systems, drawn from interviews with national stakeholders and findings that were underpinned by economic analysis geared to local contexts.

Hydrogen may be the only viable decarbonisation option for a number of industries, sectors, and end-use applications. Costs remain high but this may change dramatically over the coming decade as international interest grows due to demand and supply side factors, including higher carbon prices.

We offer some insights on how smaller, low- and middle-income countries can begin exploring the potential of hydrogen to meet decarbonisation targets, such as Paris Agreement NDCs.

Scaling up through coordination

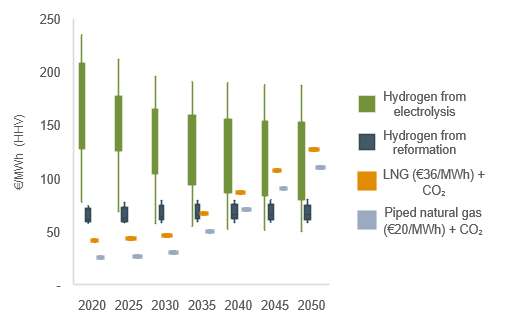

Low carbon hydrogen production remains costly and unproven at scale, whether ‘green’ hydrogen (produced by electrolysers fed by 100% renewable electricity) or ‘blue’ hydrogen (steam methane reforming with carbon capture storage). This may change dramatically over the coming decade as governments are making material commitments to developing low carbon hydrogen production capacity, particularly in relation to natural gas prices (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Low-carbon hydrogen production cost forecast, 2025-50

Source: ECA adaptation of Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, Hydrogen Production Costs 2021, compared to natural gas supply cost scenarios and applying Green Book guidance for CO2 pricing up to 2050.

However, producing hydrogen is only half the battle. The costs and logistics of delivery and storage also need consideration as they may constitute up to two-thirds of hydrogen’s final delivered cost. Scale and high utilisation can help reduce associated costs but that can be a challenge for smaller, low- and middle-income countries. For such countries, coordinating regional hydrogen projects presents a route to achieving sufficient offtake for producers. Otherwise, piecemeal low-carbon hydrogen initiatives risk stalling at the pilot project stage.

For example, the establishment of a ‘hydrogen coordination group’ among the CPs was identified as an option to help leverage regional experience, identify shared potential avenues for hydrogen, and ease alignment and cooperation with wider European energy market developments. ECA also set out five ‘cohorts’ of CP combinations and end-use applications, which can look to international examples for guidance on policy, strategy, regulation, and pilot project formation.

Finding the right context for hydrogen

The cohort approach adopted for the Energy Community analysis shows how both the local and regional context are important to consider when developing long-term hydrogen development plans. We briefly highlight the context needed to make hydrogen viable for some key applications.

Transport

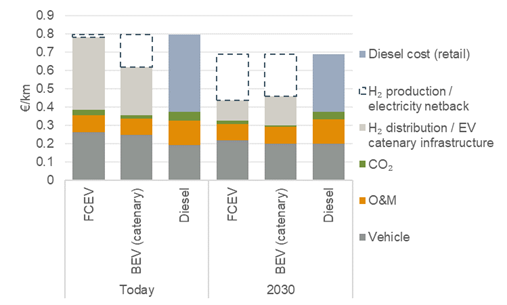

Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) may already be too far ahead of hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) in scale to decarbonise short-to-medium length transport. However, there is still likely a place for FCEVs to serve specific transport roles, namely long-distances where BEV range can struggle: heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) (see generic €/km netback calculations for FCEVs versus BEVs fed by catenary lines in Figure 2), buses, trains, and maritime shipping.

Figure 2 FCEV and BEV (catenary) HGV netback calculation (€/km)

Source: ECA analysis

Scale and high utilisation of refuelling facilities is vital to make hydrogen transport viable. Countries can coordinate to establish hydrogen refuelling infrastructure along key, cross-border transport corridors as such infrastructure will likely represent over half of hydrogen’s cost ‘at the nozzle’.

Power system flexibility

Due to efficiency losses, hydrogen-for-power is uneconomic for baseload power and large-scale batteries are likely to be preferred for short-term reserves. However, in some cases, hydrogen-fired turbines may be the only viable option to provide large-scale, low carbon power during prolonged periods of low solar and wind output. Hence, hydrogen-for-power is an option for providing long-term flexibility for electricity grids that are increasingly dependent on intermittent renewables. Electrolysers can also stack revenues by contributing to system stability through ancillary services.

The key variable is the availability of low-cost, high-volume storage. Countries can take a regional view to source geological storage or retrofit existing gas storage facilities and establish cross-border trade. Similar to transport, small-scale and poorly utilised storage could otherwise leave hydrogen-for-power prohibitively expensive.

Additional potential for isolated areas comes in the form of fuel cell units to act as an alternative to expensive diesel generation in small systems (this may be linked to off-take for transport and heat loads to leverage economies of scale).

Industrial clusters

Hydrogen extracted from fossil fuels has long been a feedstock for many industrial processes, which makes such industries a primary target for scaling-up low-carbon hydrogen. However, singular industrial sites may not be able to provide the necessary scale or utilisation rates to support production. Countries can explore developing hydrogen at ‘industrial parks’ with a variety of industrial offtake options, which can also be co-located with backup hydrogen-fired turbines and local distribution networks for heating.

With many industrial hydrogen pilot projects being explored in high-income countries, low- and middle-income countries can, to some extent, wait to find out ‘what works’ before committing to major investments. However, there remains a role for niche pilot applications, while local industries should begin exploring switching to hydrogen and clustering opportunities today. This could soon be vital to ensure access to markets that are becoming more discerning about imports’ carbon content, e.g., the EU’s development of carbon border adjustments.

Space and water heating

Hydrogen can be used to displace existing gas boilers or to compete with heat pumps for low carbon heating. The preferred option will depend on a number of factors: whether there is an existing gas network, the state of the power grid, the insulation quality of the existing housing stock, etc.

Some countries may be looking to displace biomass-based heating, or their electrical grids may struggle to cope with heat pumps, particularly in parallel with planned EV rollouts.

Hydrogen for heating may depend on the economic / technical feasibility of retrofitting existing gas pipelines, which can be an important avenue for stemming stranded asset risk across the gas sector. There are also challenging regulatory questions behind blending hydrogen in existing gas networks.

Policy tools for reaching commercial viability

Low carbon hydrogen cannot compete in today’s energy mix on cost alone. Policy can smooth the path to commercial viability.

Carbon prices are always the economist’s favoured tool to account for environmental externalities, which would directly support low carbon hydrogen. However, hydrogen’s relative inefficiency means carbon prices above €100/tCO2 are likely necessary to compete with today’s fossil fuels, which will require political support.

Drawing from experience supporting renewable electricity production, there are multiple alternative models that can help make hydrogen investments attractive and bridge the financing gap. These include payments to produce in the form of premiums or Contracts for Differences (CfDs), regulated returns (e.g., a Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model could be applied to production, as well as infrastructure), offtake obligations, or direct subsidies.

A case could be made for temporary exemptions to regulatory requirements as scaling up is prioritised over, for example, third-party access, particularly for localised hydrogen networks serving industrial clusters where trading opportunities are limited and unbundling is not feasible. Recent legislation from the European Commission appears to have paved the way for dedicated hydrogen infrastructure, including for cross-border trade, while also serving as a reference point for preferential treatment of low-carbon gases in existing gas grids through discounts on injection, storage, and cross-border tariffs.[2]

Early days…

These remain early days for the revived interest in hydrogen, but there is substantial potential for it to be a key energy vector for achieving decarbonisation if well-targeted to suitable end-use applications. Commercialisation will be a gradual process over the coming decade and low- and middle-income countries can learn from international experiences.

In the meantime, countries can follow the latest hydrogen developments, particularly the outcome of pilot projects in high income countries, explore niche opportunities for pilot project deployment, and begin developing roadmaps for a hydrogen future. Regional cooperation has the potential to ensure complementary endeavours are made to minimise overall cost. Hydrogen production costs are set to substantially decline but integrating hydrogen into energy mixes will still require a substantial degree of coordination, policy support, and creativity.

[1] Part 1: International review. Part II: Economic analysis. Part III: Contracting Party assessment. Part IV: Synthesis report.

[2] European Commission, ‘Commission proposes new EU framework to decarbonise gas markets, promote hydrogen and reduce methane emissions’, 15 December 2021.

Scott Edmonds

Managing Consultant

Scott is an economist pecialising in the economics behind energy and natural resources, particularly electricity and gas markets, and regulation. He has international experience advising governments, regulators and private sector clients in the UK, the EU, the Middle East, the Balkans, Southeast Asia and across Africa.

To contact Scott directly please email or connect with him on Linkedin below.