ECA INSIGHT >>

The concept of Just Transition, i.e. ensuring that no one is left behind in the transition to low carbon and environmentally sustainable economies and societies[1], has gained traction in the climate change context. While the term first emerged as a ‘labour-oriented’ concept in the context of defending the interests of workers impacted by the adoption of environmental regulations in the 1970s[2], it has since broadened to highlight the uneven impacts of the energy transition for affected communities and other relevant stakeholders.

The Just Transition process is, by definition, centred around energy equity, which entails access to affordable, modern and clean energy for all.[3] As such, for countries in the Global South, addressing the energy access gap cannot come as an afterthought to the objective of moving away from fossil fuels.

The Just Transition needs to be inclusive of the Global South

A Just Transition needs to be equitable and inclusive. While industrialised countries have largely achieved universal access to electricity and are now focused on decarbonising their energy systems, many developing countries still struggle with significant energy access gaps and high levels of energy poverty.[4] Given that these countries are also particularly vulnerable to climate change, access to energy becomes crucial for their ability to adapt to climate shocks, through climate-smart storage and agriculture. Before these countries can meaningfully embark on decarbonisation efforts, they must first address the pressing need to provide universal access to reliable and affordable electricity, which poses significant challenges[5]:

- Those still lacking access are becoming harder to reach because they live in more remote areas, have lower incomes and are concentrated in the least-developed countries, affected by fragility, conflict, and violence.

- There is no viable path to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) without accelerated deployment of decentralised solutions, yet current investment in the sector falls far short of what is required for scale-up.

- Under current scenarios, 660 million people will still lack access in 2030, 85 percent of them in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The Just Transition requires a nuanced approach that aligns with the priorities and unique developmental circumstances of each region

In this context, it is worth considering whether the concept of Just Transition is helpful in the Global South’s climate policy and whether it adequately captures the context-specific nature of the transitions, and particularly the energy access challenge. As stakeholders from affected communities in Colombia, Ghana and Indonesia have noted, the term ‘felt detached from the realities of communities that prioritise access to affordable energy over emissions reduction’.[6]

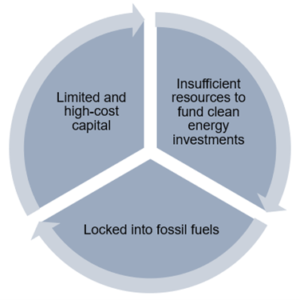

Countries in the Global South are entrapped in a vicious cycle (shown in Figure 1), whereby, due to the prohibitively high upfront cost of clean energy, they end up being locked into fossil fuel projects; in other words, the poverty trap becomes an energy trap, which then becomes a climate trap.[7]

Figure 1 The vicious cycle of the energy transition in the Global South

Source: Adapted from World Bank. 2023. Scaling Up to Phase Down: Financing Energy Transitions in the Power Sector.

Due to limited and high-cost capital, countries in the Global South are unable to break away from the vicious cycle towards projects that contribute to development and climate objectives. According to the World Bank, a just transition that is consistent with both SDG7 and the Paris Agreement would require power sector investment in low- and middle-income countries (excluding China) to quadruple from an average of $240 billion annually in 2016-2020 to $1 trillion in 2030.[8]

The Just Transition needs to address distributional justice concerns

Not only does energy access need to be a central pillar of any transition strategy to ensure that the Global South is not left behind; a Just Transition also needs to ensure that any positive benefits are distributed equitably within local communities. This is crucial as the world is becoming increasingly reliant on energy transition minerals that are used in renewable technology; for instance, lithium, nickel and cobalt are core components of the batteries for electric vehicles. As the market for these minerals is growing[9], there is a powerful opportunity for increasing energy access and improving livelihoods in communities that are resource abundant.

However, the transition does not seem to have delivered positive outcomes for the affected communities; in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which produces most of the cobalt, the energy access rate for the rural population in 2022 was 12.6%,[10] making it the country with the second largest energy access gap in 2022 (78 million).[11] Historically, power capacity has been built to supply mining facilities, with more than half of the electricity consumed in the country being used by the industry, rather than for providing access to households and businesses.[12] In light of this challenge, the DRC government is seeking to increase electricity connections by appealing for development funding and mandating that electricity companies provide power to the population in addition to mining companies.[13] Similarly, concerns about the impact of the energy transition on livelihoods are predominant in the North Morowali region on Indonesia’s Sulawesi Island, which hosts some of the country’s largest nickel deposits.[14]

The Just Transition concept can help frame the dialogue around the uneven impacts of the shift away from fossil fuels. However, it needs to be inclusive and aligned with the specific challenges facing each region’s energy transition path. In the context of the minerals industry, the development of transition strategies needs to consider the issues faced by vulnerable groups in mining communities[15] and ensure that the long-term aim of the transition is compatible with the near-term objectives of energy access, job creation and improved livelihoods.

[1] UN Committee for Development Policy. 2023. Just Transition.

[2] Wang and Lo. 2021. Just transition: A conceptual review.

[3]World Economic Forum. 2024. Building Trust through an Equitable and Inclusive Energy Transition.

[4] South to South Just Transitions. 2022. Exploring Just Transition in the Global South.

[5] Tracking SDG7. The Energy Progress Report 2024.

[6] Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. 2023. Engaging communities in a just transition.

[7] World Bank. 2023. Breaking Down Barriers to Clean Energy Transition.

[8] World Bank. 2023. Scaling Up to Phase Down: Financing Energy Transitions in the Power Sector.

[9] UN Environment Programme. 2024. What are energy transition minerals and how can they unlock the clean energy age?

[10] World Bank. Access to electricity, rural. DRC.

[11] Tracking SDG7. The Energy Progress Report 2024.

[12] The Carbon Brief Profile: Democratic Republic of the Congo

[13] US International Trade Administration. Democratic Republic of Congo. Country Commercial Guide.

[14] Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. 2023. Engaging communities in a just transition.

[15] Shiquan et al. 2022. The impact of mineral resource extraction on communities: How the vulnerable are harmed.

Iro Sala

Consultant

Joining ECA in September 2021, Iro focuses on rural electrification in Africa’s off-grid sector, establishing best practices for sustainable public institution electrification and assessing public funding for off-grid solar. Holding an MPhil in Economics from Oxford and a BSc in PPE from King’s College London (where she researched gentrification in London), she specialized in urban-spatial, public, and behavioral economics, with her thesis analyzing regulatory competition and firm mobility in Europe.